- Going Beyond Music with a Gathering of 100,000 in 1972

On August 20, 1972, Stax Records organized a remarkable concert in Los Angeles, showcasing their top artists. This extraordinary event, known as “Wattstax,” is now being celebrated with the release of a new box set and a theatrical reissue of a documentary from 1973. However, comprehending the significance of this momentous occasion requires us to rewind our timeline back to August 1965.

During a Stax revue performance at the renowned 5/4 ballroom in Watts, Los Angeles, Carla Thomas took the stage. Following the show, she encountered a young fan named Jacqui Jacquette, who had recently won a local talent competition by singing Thomas’s 1961 hit “Gee Whiz.” Jacquette extended an invitation to Thomas, inviting her to join her family for dinner. The following day, they embarked on a sightseeing excursion, which Thomas fondly recalls. She recounts, “We visited a small shopping center where there was a humble office where young individuals were being taught passive resistance, similar to the training undergone by the Freedom Riders.”

As their visit neared its end, Jacquette revealed the reason behind the training. “They are targeting young Black men,” she expressed, referring to the police. Several days later, the arrest of Marquette Frye, a 21-year-old African American, pushed the community to its breaking point. The ensuing six days witnessed widespread uprisings that resulted in numerous casualties, thousands injured, and extensive property damage amounting to tens of millions of dollars. Regrettably, news coverage at the time skewed public perception, focusing more on the unrest itself rather than the underlying causes.

- Celebrating Black Heritage: The Legacy of Wattstax

In commemoration of the uprisings’ first anniversary, Tommy Jacquette, cousin of Jacqui, played a pivotal role in launching the Watts Summer Festival. This annual event aimed to rebuild the community and pay tribute to those who had lost their lives. Music writer Rob Bowman notes that the festival reached new heights in its seventh year when Memphis-based Stax Records got involved.

By 1972, Stax had set up a satellite office in Los Angeles, with the goal of promoting their existing artists, discovering new talent, and establishing a presence in the television and film industries. However, co-owner Al Bell had a grander vision. He recognized that the company’s work centered around Black expressive culture, and he believed that Stax had a responsibility to the community.

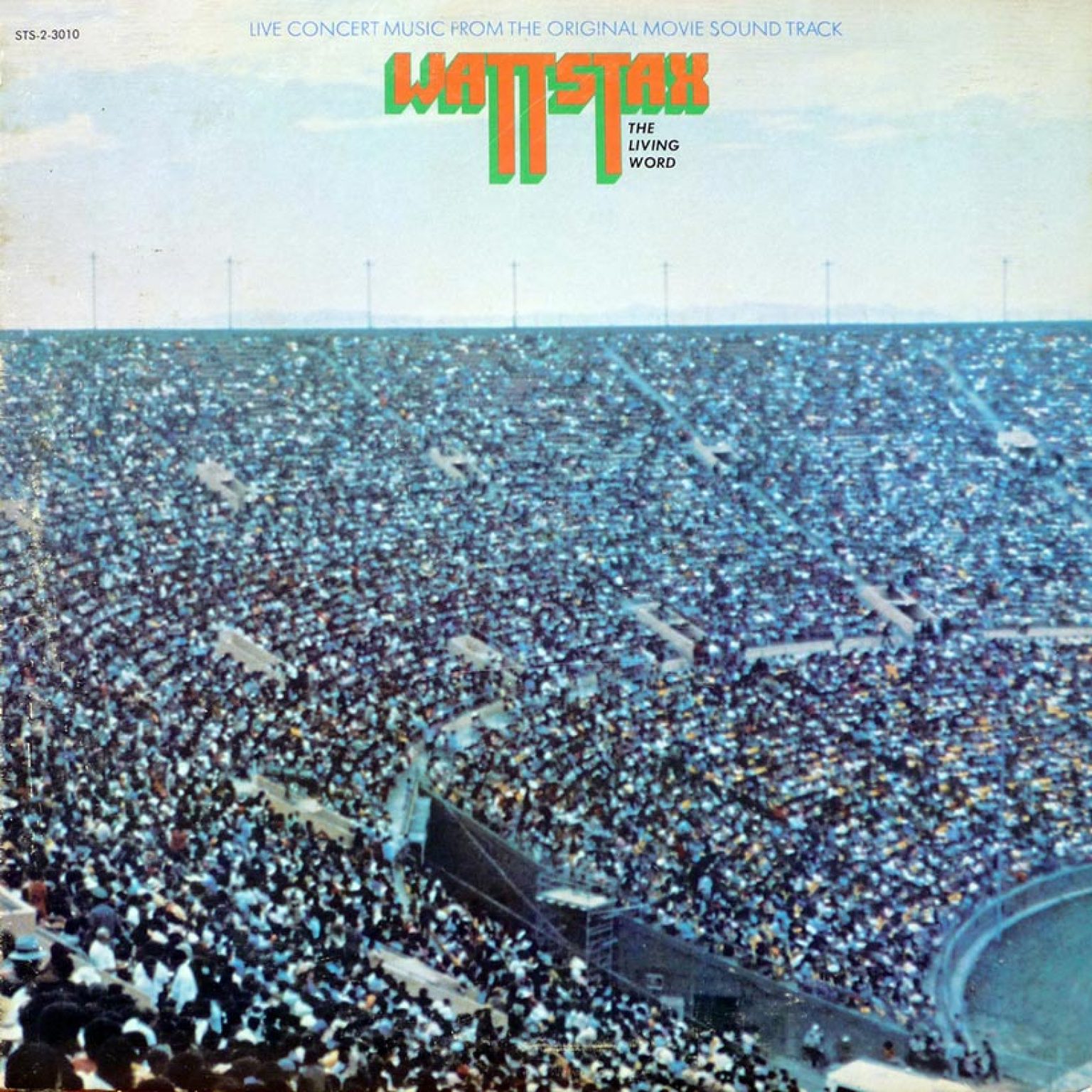

Bell, alongside Tommy Jacquette and Forest Hamilton, Stax’s West Coast director, embarked on the ambitious task of organizing a large-scale benefit concert to conclude the 1972 Watts Summer Festival. This initiative came to be known as “Wattstax.” The label secured the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum as the venue and enlisted numerous Stax artists. The concert’s promotion involved door hangers, billboards, and airplane banners. Bell wanted the community to understand that Wattstax was more than just entertainment; it was a celebration of the African-American experience and a testament to the transformative power of music.

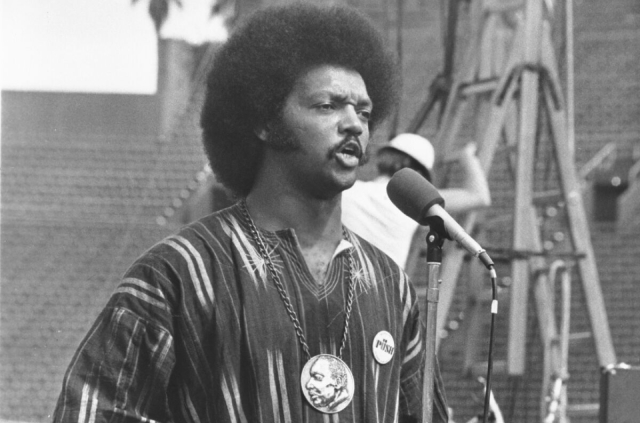

On August 20, 1972, over 100,000 people flocked to the event, making it the second-largest gathering of its kind after the 1963 March on Washington led by Martin Luther King Jr. Rev. Jesse Jackson set the tone for the day’s proceedings with his powerful recitation of “I Am Somebody.” Kim Weston then delivered a stirring rendition of “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” often referred to as the Black National Anthem. Over the next seven hours, gospel, R&B, funk, and soul music resonated throughout the venue, featuring performances by renowned artists such as the Staple Singers, Isaac Hayes, the Bar-Kays, Carla Thomas, and Rufus Thomas, who encouraged the audience to let loose and “get on up.”

In this article

Bell’s decision to set ticket prices at only one dollar allowed people from all walks of life to experience the inspirational, healing, and unifying power of music. The concert resembled a family reunion, attracting attendees of all ages, from young children to grandparents. It created an atmosphere akin to a spiritual church service, fostering profound connections within the Watts community and beyond. Carla Thomas describes the concert as a deeply spiritual moment due to its message of rebuilding Watts, its connection with the community, and the profound impact it had on the world.

Wattstax raised over $70,000 in support of various causes, including the Watts Summer Festival, the Sickle Cell Anemia Foundation, and the Watts Labor Community Action Committee. The release of a double album featuring concert highlights sold over half a million copies within weeks. However, Bell desired to extend the message of Wattstax beyond Black audiences and reach white communities as well.

Recognizing the prevailing fear and stereotypes that often surrounded Black individuals, Bell aimed to counter these biases and present an authentic representation of the African-American experience. To achieve this, he decided to film the concert and collaborate with producers David L. Wolper, Larry Shaw, and director Mel Stuart. Despite limited opportunities for Black crew members in Hollywood, Bell ensured that the team behind the documentary was predominantly Black. Instead of relying on pundits, the filmmakers returned to Watts and captured The Emotions singing in a church, Richard Pryor providing insightful commentary on race relations, and everyday people (including a pre-famous Ted Lange) engaging in conversations at barbershops, street corners, and diners. These vignettes, interspersed with concert footage, depicted the struggles, resilience, and joy experienced by the community.

TheStaplesSingers 1

TheStaplesSingers 1

The Wattstax documentary, released in 1973, received critical acclaim and was showcased at Cannes. It was also nominated for a Golden Globe and, in 2020, was added to the National Film Registry. While the fight for racial equality continues, Bell believes that Wattstax, which took place half a century ago, still embodies the hope for a better future. “There was one spirit and attitude that prevailed. It was the spirit of love.”

DISCLOSURE: This post may contain affiliate links, meaning we get a commission if you decide to make a purchase through our links, at no cost to you. Please read our DISCLOSURE for more info.

You may also like

We Love “Here I Come” by Barrington Levy

Barrington Levy’s signature hook and his original song “Here I Come” was a big hit

Jamming to Aretha Franklin’s “Jump”

Jamming to Aretha Franklin’s “Jump” “Jump” was part of the Warner Bros. film "Sparkle and

Black Cinema Month: Cooley High – Part 2

This film had the saddest song many people had ever heard. Now we can’t talk